Makerspaces provide new affordances for learners and creative types to explore new and exciting branches of learning, creating and exploring from 3-D printing, e-textiles to computer-assisted-design. This leads me to wonder about the role or best stance for educators in this environment. According to Barniskis (2014),

“…many teachers are used to teaching a large group of children to work on one project at a time. However, in a makerspace environment, each student may be working with different tools and processes. The teacher needs to be comfortable with a considerable quantity of chaos in such an environment, as well as skilled with all of the tools and able to switch gears quickly.” (p. 6)

In particular, it is the “switching gears” where educators assess learner proficiencies to inform next steps that is the subject of this paper. First, we’ll examine makerspaces pedagogies and consider the teacher’s/facilitator/coaches role, then explore and analyze the use of “traditional” assessment strategies in makerspaces, and finally, suggest three assessment strategies that seem well matched within a makerspace. Overall, we will consider the role of assessment in makerspaces and how does it need to be modified or adapted in this setting to help our makers?

Makerspace Pedagogies

In makerspaces, the role of learner has evolved from a passive recipient of information to the learner as an active creator and/or maker. The new affordances like 3-D printers, programmable robots, e-textiles, among many others provide a new and increasingly complex canvas for digital designers to build and make. With externals like MakeyMakey, Lego WeDo or Mindstorms, a makerspace can also be an environment that encourages makers and creators to computer program using languages from with “low floor” like block-based Scratch, or text-based Arduino or beyond. Yet, even with these tools that encourage creativity and design where students and makers might pursue their own projects, the role of the coach/educator/facilitator is crucial. They can encourage students to not only learn new skills but also feel comfortable and confident to create, make and perhaps even innovate. Striking a balance between teaching established and traditional elements and principles of design and also encouraging them to innovate can be tricky. The role, stance and practices of the educator are critical so that makerspaces can become a unique place for creativity and design and not simply another room where a specific a set of instructions are “delivered”, then copied and then assessed. Perhaps in critically examining our assessment and evaluation practices we can find approaches and practices that best support our makers and creators in makerspaces.

Current Assessment strategies

Being evaluated is a key and yet sometimes challenging experience for most students (and perhaps everyone) historically and today. Yet educators acting as mentors can have a vital role in helping others develop their ideas and improve the design and functionality of prototypes. The role of mentors or coaches requires a modified approach than a traditional – teach then evaluate model. A review of makerspace literature and research seems to indicate that traditional evaluation and assessment methods continue to be considered as indicators of progress. For example, in some studies, the focus of assessment has been less on creativity and more on specific measureable outcomes determined beforehand by the teachers and curriculum designers. While determining key concepts and core fluencies is critical, perhaps a more flexible learner-centered approach would seem to be a better strategy than one based on immoveable standards. This is especially important in spaces that encourage creativity, innovation, design and perhaps arts. In regard to e-textiles, Peppler (2013) emphasizes art first “… that the e-textile designer is less concerned with coding efficiency—having as few lines of code as possible—than with achieving a particular artistic effect” (p. 38). Assessment remains a critical strategy to help mentor our makers and creators to extend their learning through their Zone of Proximal Development. (McLeod, S. A. 2012 para. 1). Yet in some studies, the justification for makerspaces seems to fall back on numbers to quantify students’ outcomes and progress.

“When we analyzed their final Scratch programs using Brennan and Resnick’s computational thinking framework [2], we found that 100% of the projects used sequential statements, loops, conditional statements, event handling, and 85.7% (or 6/7) of the projects used operators.” (Davis, 2013, p. 440).

Here is another example “…when the multimeter was used, boys had the equipment in their hands 75% of the time on average to only 25% for girls.” (Buchholz et al., 2012, p. 283).

These quotations seem to focus on specific quantitative measurements (i.e. use of specific computer science skills and use of a specific tool by gender.) Both these measurements are important as ONE form of analysis yet neither evaluation indicates a focus on creativity or innovation. Furthermore, they may actually be only a small step from a mark-based assessment with such narrow focus. For example, a student might earn an “A” mark for simply including a certain amount of loops in their project. Perhaps a model where students and teachers negotiate shared objectives would encourage more creativity. Kohn (2011) seems to reject any traditional form of teacher determined grades in educational spaces saying instead “…students can be invited to participate in that process either as a negotiation (such that the teacher has the final say)…” (p. 6). No doubt, the promotion of computational thinking and gender equality are critically important indicators for success, but perhaps assessment in makerspaces should be specifically focused on creativity, innovation and digital citizenship (helping others) above other specific technical requirements. In other words, a successful project might not include all the computational requirements nor be in the hands of a specific gender and still produce a creative and innovative prototype. Perhaps then assessment strategies should focus away from marks as indicators and instead look towards more qualitative methods that demonstrate a maker’s thinking and detailed progress. In addition, it is unclear whether a grade reflects the “potential” of an idea or a “snapshot” of the project at that time. Subsequently, this type of mark-based assessment in quantifiable terms obscures rather reveals student progress, creativity and potential.

Three Methods of Assessments

Perhaps makers and educators might instead work collaboratively to critically evaluate designs based on principles like Design Thinking that encourage both process and final product through a variety of activities and practices. Based on research into makerspaces and practices, three types of assessment tools seem to be good fits for makerspaces: design journals, reflections and badging.

Design Journals

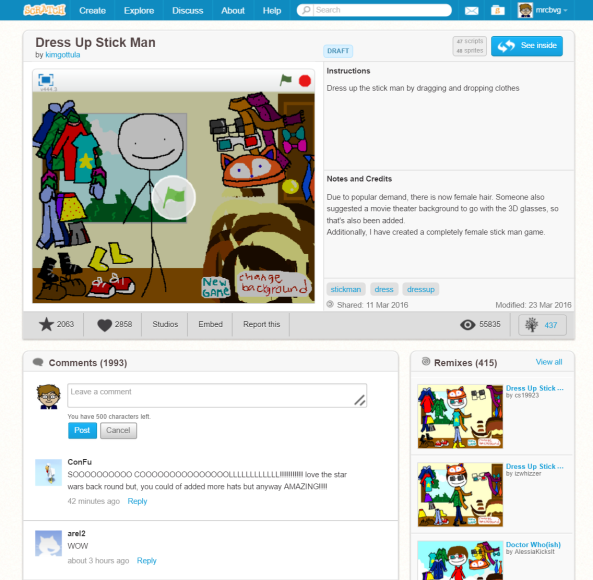

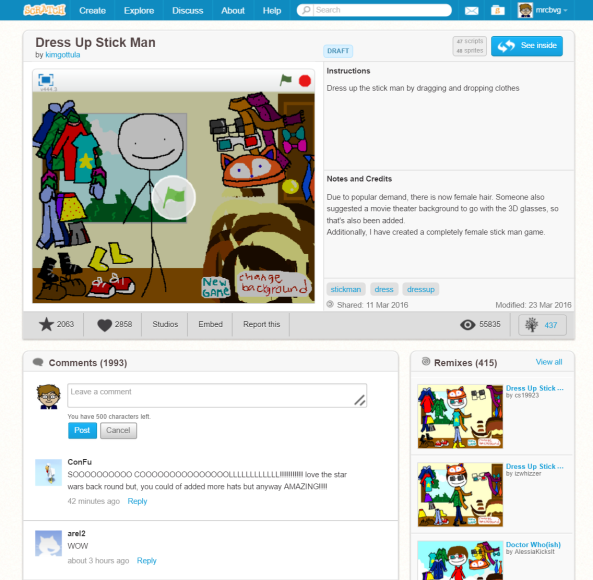

A design journal can be either physical or digital and is a place to notes and instructions about a particular prototype or program. With prompting, students can not only write about the process but also be prompted to engage in new forms of thinking and processes like design thinking. Design thinking is an excellent process to solve challenges and promotes a similar mindset to makerspaces with its emphasis on creativity, design and iteration. One excellent example of a design journal is found in the project page of in the web-based Scratch 2.0 site. Scratch is an excellent tool for block-based coding and has both Papert’s “low floor (easy to get started) and high ceiling (can be used for increasingly complex projects). (Resnick, 2009, p.63). In addition to a page to create block-based commands is a project page which could be a design journal. Each project page (Figure One below) has three sections for writing: instructions, notes and credits and a comments stream. The first area provides a place for instructions critical for those wanting to run the Scratch program. This area explores the use of each sprite, backgrounds and other commands.

Example of a Design Journal Figure One

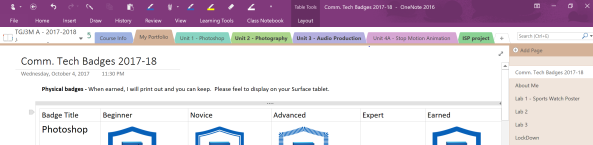

The Notes and Credits section provides a place for the programmer to comment upon the design of the program including sources for resources used, a brief summary of their thinking, current progress and next possible steps. These possible next steps might be influenced by the comments section (which can be toggled on or off) by fellow programmers and Scratch users to provide feedback for the original programmers. Comments have the potential to be a shared and logged conversation about programming and specifically Scratch. In its highest level, it is collectivism where programmers and designer collect their best ideas on programming and designs in the Scratch forums. In Scratch, an ultimate form of flattery is the re-mix where programmers make a copy and tinker with a new iteration of the program which also includes a vital and transparent record of the original creator. This “built-in” design journal provides excellent opportunities for assessment as educators can observe not only the program but the programmer’s dialogue with themselves and others. Educators could even join in the collective conversation embedded directly in the project with comments, suggestions and encouragement of their own. According to Nichols (2015), “as students document their thinking they are supported by community partners who act as mentors to promote their thinking and give them the real-world exposure and experience they need to overcome challenges” (para. 5). Nichols calls them “thought-books” and they could serve as a hybrid design journal and place for reflective writing. It is important to note that design journals could be in many different forms from traditional physical books to more sophisticated online creations like the OneNote Class Notebooks. (See Figure Two below for an example from one of my classes).

OneNote Class Notebooks provide a sophisticated tool for designers and educators as the digital format would allow the curation of a notebook that could include embedded physical sketches, notes, photos, animations, documents, videos, links to 3-D designs (i.e. Tinkercad) and even involve audio and video conversation as either a shared private conversation or even public if shared online. Perhaps the OneNote ClassNotebook moves the Design Journal up the ladder up in the SAMR model on technology integration from the substitution ring towards the augmentation or modification stages. (Puentedura, 2014, p. 2). Not to suggest that this amount of complex technology tools are always necessary and may even “get in the way” through diverting focus. After the potentially and rightfully “messy” of a design journal, the next assessment tool for educators allows for more focus on thoughts and words.

Reflective writing

For more depth into the thinking of learners in makerspaces, reflective writing could be another assessment tool for educators to explore the metacognition of makers and creators. Using tools like physical notebooks or even digital forms like blogs, makers and creators share their goals, process and experiences from their perspectives. If this reflective writing is shared, then educators and mentors can potentially have insight into the “black box” that is a learner’s thinking. Access to this form of writing allows mentors and educators to help learners “level up” and reach the next stage for their progress or even when to “move on” to something new in the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). In short, makers and learners need to focus on the process being as important (or perhaps more) than a “final” product. Reflective thinking and writing should take place at various points (say beginning, during and end) as creation and making is occurring so that educators can see the process of student thinking and suggest next steps or extend thinking further when needed. Educators and mentors can leverage reflective writing of makers and creators to provide feedback in the form of constructive dialogue. They can also use this tool to plan next sessions and provide learning materials and guidance for the specific needs of makers and learners. Indications of progress and identifying next steps are part of the final assessment strategy using badging.

Badging

The awarding and distribution of badging can be one way to facilitate the conversation between makers and mentors through the awarding, earning and sharing of micro-credentials. “Digital badging recognizes learning and growth wherever it happens and helps people connect their accomplishments across institution types.“ (Fontichiaro, 2015, What is digital badging? para 2) Digital or physical badging has the potential to recognize and indicate learning outside of traditional classes and in unique environments like makerspaces. These tools are new to education but have been successfully used in organizations like Scouts or even objective-based video games. In other words, some students would have prior experience with badging in both physical and digital badges forms. However, bringing this assessment into the new and evolving “anywhere classroom” including a makerspace offers new opportunities for learners and educators to record their progress.

Badging could be an excellent indicator of the wide variety of skills, abilities and progress made by learners in a makerspace. However, there are a few criticisms that should be examined before utilizing badging for our makers. Some like Seliskar have cited badges as a motivating tool, yet I think that using badges only to motivate could have the opposite effect. (2014, para. 1) They might serve as a motivator in the short term but might be better served as a digital indicator of learner progress as issued by educators, mentors and specialists. The idea of a “badge economy” is a much more powerful concept with a longer timeframe as they provide a record of subject or skill mastery. In a “badge economy” student earns a backpack of badges with each carrying everything needed (i.e. metadata) to understand the badge (who gave it, what is it for etc.) Sunny Lee, a product manager from Mozilla suggests that “(t)he digital backpack enables the learner to be able to curate and manage the image that they want to represent to the rest of the world…the idea is that we’re kind of laying down the plumbing for this badge economy to flourish. Now, we need some badges circulating around the economy to jumpstart it.” (Ash, 2012, p.28) Makerspaces would seem ripe for the creation of many badges (i.e. mBot programmer) that learners could add to their backpack. (See Figure Three below for example badges.)

| Figure Three Sample badges |

In this assessment model, students acquire key knowledge from a curated list by educators, curriculum designers or specialists in order to earn teacher-created badges. Teacher created badges are essential as they could serve as indicators for makers/creators or programmers to “level-up” their skills. For example, educators could indicate and celebrate students’ initial progress on a particular tool (i.e. Level One) but create a scale to encourage them to explore the tool and their own creativity in more detail (i.e. Level Two…) According to Grier, “… the best approach to scaling digital badging is not to focus on students, but on their teachers.” (2015, para 3). Teachers can provide the expertise to encourage next steps and extend thinking.

Perhaps an even more student-centered approach is a co-creation model between learners and educators to create a unique learning pathway for makers. This co-creating model has the potential for students to demonstrate core competencies but leaves room for creativity and innovation so critical to leveraging the potential of makerspaces. Like “stepping stones’, learners navigate their progress throughout a specific area of focus with badges as indicators and then earners decide to keep private or share (with interested parties) along the way. Teachers might help students create a “…portfolio that reflects the skills and knowledge they have developed, as well as evidence…” (Grier, 2015, para. 11).

These badges could then be shared online at the discretion of the badge earners. Ash states that “…the badge earner must be responsible for managing his or her own badges.” (2012, p. 28). Putting the sharing permissions in the hands of the learner is critical as no doubt in their mind or the minds of others (institutions, employers, even peers etc.) some badges will have more weight than others. This is certainly a valid criticism but the metadata in each badge will indicate the date, issuer and skills learned and demonstrated for clarity. This metadata is a clear indicator of learner’s progress with sharing permissions at the discretion of the learner. The transferrable and sharing potential for badges through sites like credly.com or badgelist.com and housed on wikis, blogs or websites provides new opportunities for learners to share their progress, learning and success. This not only allows learners to find success but also to create a strong digital footprint potentially leading to future learning and collaboration opportunities in global settings. The Mozilla Open Badges might provide this global setting as place for learners to collect badges earned and issuers to add badges in a learner’s digital “backpack”. (See Figure Four below) However, the appealing nature of the issuing of these micro-credentials is that earners can decide to showcase and share the progress and achievement through the web to interested parties (i.e. recruitment for makers) in global market place of the internet.

Figure Four – Sample from digital backpack or eportfolio

More on Collaborative Assessment

Collaboration beyond student- teacher relationship also offers opportunities for makerspaces. The successful collaboration of educators, curriculum designers, researchers and specialists will aid learning environments and makerspaces that emphasize design and making through varied perspectives on student progress and perspectives. “If teaching artists partner with the shop teachers, home education teachers, and computer science educators in schools, a multifaceted makerspace can emerge.” (Barniskis, 2014, p. 7) Makerspaces can be a good gathering point for conversations between learners with many different types of specialists and experts on next steps and sharing of progress.

Design journals, reflective writing or badging need not be public but can be the basis for crucial conversations concerning next steps between makers and peers or makers and mentors. Educators might plan out time for makers to have these conversations which will only help the makers in their learning but also provide evidence for educators on the progress of students. Even the conversation could be used for assessment, which might be recorded through a page in a design journal, written reflection or even a badge. Making a “pitch” and hearing feedback from peers or experts are an important element in the design thinking toolkit for educators and makers.

Finally, conversations with other parents, guardians and other important figures in a student’s life can have an impact on learning and assessment as educators gain a wider perspective of student progress. Creating connections between home and school through open communication between educators, parents and students can be important to help educators create authentic experiences for students to learn and make progress.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Based on research into makerspaces and practices, three types of assessment tools seem to be a good fits for makerspaces: design journals, reflections and badging. Design journal and reflective writing are two strategies that emphasis metacognition and encourage learners to self-evaluate their progress in makerspaces. Learners can then choose what to keep private, or share with peers in a co-learning or collaborative structure and finally, engage with experts globally. Use of reflections at different stages of projects with a variety of audiences can also be critical to encourage increasing authentic feedback, assessment and evaluation for makers. Reflective writing and design journals are powerful tools for design thinking strategies. Badging is another pedagogical strategy that might serve to clearly indicate the desired outcomes (i.e. design, computer science as well as an implied gender balance) and yet encourage students to explore a breadth (and depth) of maker tools in an open-ended way. In addition, these forms of assessment are easily incorporated into design club routines and workflow. (see Figure Five below) If makerspaces offer new pedagogy and opportunities for students, then challenging and critically evaluating our assessment practices is vital if we are to encourage student success and innovation.

Figure Five Workflow model

In terms of assessment, I do not mean to suggest that creativity and innovation should be the only focus in a makerspace as no doubt equitable access, student enthusiasm, gender equality, computational thinking, curriculum expectations, digital citizenship are vital. In fact, the powerful affordances in makerspaces may even allow makers to make progress regardless of the stance of educators. However, switching between a teacher-centered to student-centered stance and using assessment practices like design journals, reflections and badging allow for mentors and educators to better explore the “black box” that is the mind of the makers. These tools could provide the necessary support for makers to grow and flourish. According to Fessakis et al. (2013) “… the teacher’s role during the proposed learning activities (computational) was critical. She encouraged and supported the children to overcome their difficulties, controlled the various coordination issues that came up (e.g. the next player’s turn) and handled the cases where the children seemed not to be able to deal successfully with.“ (p.86). Overall, makerspaces offer learners to opportunities create a unique pathway with new and exciting experiences for learners and mentors who can support, assess and even co- learn.

References

Ash, K. (2012, June 13). Colleges Use ‘Digital Badges’ to Replace Traditional Grading. Digital Directions, 05(03), 26. Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/dd/articles/2012/06/13/03badges.h05.html?tkn=SPOFHItvuFGEOUO0jyGFYbA5FMSXhWNiR5R8&print=1c

Barniskis, Shannon, Crawford (2014). Makerspaces and Teaching Artists, Teaching Artist Journal, 12:1, 6-14, DOI: 10.1080/15411796.2014.844621 retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com.uproxy.library.dc-uoit.ca/doi/pdf/10.1080/15411796.2014.844621

Culutta, Richard. (2011). Zone of Proximal Development. retrieved from <http://www.innovativelearning.com/educational_psychology/development/zone-of-proximal-development.html>.

Davis, R., Kafai, Y., Vasudevan, V., & Lee, E. (2013). The education arcade: Crafting, remixing, and playing with controllers for Scratch games. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, 439-442. New York: ACM. doi: 10.1145/2485760.2485846

Fessakis, G., Gouli, E., & Mavroudi, E. (2013). Problem Solving by 5-6 Year Old Kindergarten Children in a Computer Programming Environment: A Case Study. Computers & Education, 63, pp. 87 – 97.

Fontichiaro, Kristin, and Angela Elkordy. (2015 26 Mar). Chart Students’ Growth with Digital Badges ISTE. Retrieved from https://www.iste.org/explore/articleDetail?article=Chart%2Bstudents%2Bgrowth%2Bwith%2Bdigital%2Bbadges&articleid=320&category=In-the-classroom>.

Gerstein, Jackie, (2013, March 16th) I Don’t Get Digital Badges. Retrieved from https://usergeneratededucation.wordpress.com/2013/03/16/i-dont-get-digital-badges/

Grier, Terry. (2015, 31 Oct.). So You Want to Drive Instruction With Digital Badges? Start With the Teachers. EdSurge News. Retrieved from https://www.edsurge.com/news/2015-10-31-so-you-want-to-drive-instruction-with-digital-badges-start-with-the-teachers.

Horvath, Joan and Cameron, Rich, (2015, May 5th). The New Shop Class: Getting Started with 3D Printing, Arduino, and Wearable Tech, Apress, Technology in Action

Ito, Mizuko, Kris Gutiérrez, Sonia Livingstone, Bill Penuel, Jean Rhodes, Katie Salen, Juliet Schor, Julian Sefton-Green, S. Craig Watkins. (2013). Connected Learning: An Agenda for Research and Design. Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Kohn, Alfie. (2011) The Case Against Grades. Educational Leadership: November 2011, Retrieved from http://www.alfiekohn.org/article/case-grades

McLeod, S. A. (2012). Zone of Proximal Development. Retrieved from www.simplypsychology.org/Zone-of-Proximal-Development.html

Moura, Karly, (2016, January 17th) Gamifying our STEM Lab Challenges. Retrieved from http://karlymoura.blogspot.ca/2016/01/gamifying-our-stem-lab-challenges.html

Nichols, Garth. (2015 Sept. 10th) Inquiry & Design Lab. The Teachers Guild. https://collaborate.teachersguild.org/challenge/how-might-we-create-rituals-and-routines-that-establish-a-culture-of-innovation-in-our-classrooms-and-schools/ideas/inquiry-design-lab>.

Ostashewski, N., Reid, E., and Reid, D., (2014). Introducing 3D Printing to the classroom using inquiry: A case study describing implementation, challenges and successes. pp 1597-1605 EdMedia Tampere, Finland

Puentedura, Ruben R. (2014, November 12th) SAMR: First Steps. Retrieved from http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2014/11/13/SAMR_FirstSteps.pdf

Seliskar, Holli Vah. (2014, May 16th). Using Badges in the Classroom to Motivate Learning.” Faculty Focus. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-with-technology-articles/using-badges-classroom-motivate-learning/.

Siko et al. (2013). Disappearing Future 2. Educational Processes. Retrieved from http://www.wfs.org/futurist/2013-issues-futurist/september-october-2013-vol-47-no-5/top-10-disappearing-futures/disap-0

Turri, Dan et al. (2013). Disappearing Future 2. Educational Processes. September-October-2013 Vol.47-No.5

Resnick et. al. (2009). Scratch: Programming for All. Communications of the ACM November 2009 Vol. 52, No. 11, p. 60 – 67 Retrieved from http://web.media.mit.edu/~mres/papers/Scratch-CACM-final.pdf

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wiley, David. (2012, June 12th) Iterating towards Openness. Retrieved from http://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2397